Guidelines on the assessment of data breaches under Part 6A of the PPIP Act

Read the document below or download it here: Guideline - Guidelines on the assessment of data breaches under Part 6A of the PPIP Act September 2023

Guidelines on the assessment of data breaches under Part 6A of the PPIP Act

Part 6A of the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 (NSW) (PPIP Act), establishes the Mandatory Notification of Data Breach scheme. Under the scheme, all public sector agencies bound by the PPIP Act must notify the Privacy Commissioner and affected individuals of data breaches involving personal or health information that are likely to result in serious harm.

The Privacy Commissioner is empowered under section 59ZI to make guidelines for the purpose of exercising the Commissioner’s functions under Part 6A.

These Guidelines, made in accordance with that section of the PPIP Act, are intended to provide agencies with guidance on:

- the process of undertaking an assessment to determine whether an eligible data breach has occurred, and

- the factors to consider when assessing where serious harm to affected individuals is likely to result from a data breach.

These Guidelines supplement the provisions of the PPIP Act. Agencies must have regard to them in accordance with section 59I of the PPIP Act.

Sonia Minutillo

A/Privacy Commissioner

Information and Privacy Commission NSW

September 2023

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Part 6A of the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 (NSW) (PPIP Act), establishes a scheme for the mandatory notification of data breaches by NSW public sector agencies.

Under the Mandatory Notification of Data Breach (MNDB) scheme all public sector agencies (agencies) bound by the PPIP Act must notify the Privacy Commissioner and affected individuals of data breaches involving personal or health information that are likely to result in serious harm unless an exemption applies. More information on exemptions is provided in sections 1.2 and 3.1.7.

The MNDB scheme requires agencies to have regard to any guidelines issued by the Commissioner when assessing a data breach.[1]

These Guidelines on the assessment of data breaches (Guidelines) have been made under section 59ZI of the PPIP Act.

These Guidelines are designed to help agencies recognise circumstances that trigger obligations under the MNDB scheme. They also provide further clarification on what constitutes an eligible data breach.

Agencies must have regard to these guidelines; however, they are not legal advice. Agencies are encouraged to seek professional advice tailored to their own circumstances where required.

Examples are provided throughout the guidelines. These examples are not exhaustive and should be considered as illustrative only.

1.2 Other resources

These Guidelines are part of a suite of guidelines and resources the IPC has developed to help agencies ensure they have the required systems, processes and capability in place, and should be used in conjunction with the following additional materials:

- Guide to Preparing a Data Breach Policy

- Guide to managing data breaches in accordance with the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 (NSW)

- Guidelines on the exemption for risk of serious harm to health or safety under section 59W

- Guidelines on the exemption for compromised cyber security under section 59X

- Mandatory Notification of Data Breach Scheme webpage

2. Understanding assessment obligations

This section of the Guidelines provides agencies with guidance on how to interpret the key words and concepts used in the MNDB Scheme when assessing whether a eligible data breach has occurred. The Guide to managing data breaches in accordance with the PPIP Act provides further discussion and examples.

2.1 What is a data breach?

2.2 What is an eligible data breach?

The MNDB Scheme applies where an ‘eligible data breach’ has occurred.

For a data breach to constitute an ‘eligible data breach’ under the MNDB Scheme there are two tests to be satisfied:

- There is an unauthorised access to, or unauthorised disclosure of, personal information held by a public sector agency or there is a loss of personal information held by a public sector agency in circumstances that are likely to result in unauthorised access to, or unauthorised disclosure of, the information, and

- A reasonable person would conclude that the access or disclosure of the information would be likely to result in serious harm to an individual to whom the information relates.[2]

Whether non-compliance with the IPPs or HPPs by an agency may constitute an eligible data breach will depend on whether the non-compliance meet the tests outlined above.[3]

1.3 Personal and health information

The MNDB scheme applies to breaches of ‘personal information’ as defined in section 4 of the PPIP Act.

For the purposes of Part 6A of the PPIP Act the definition of personal information also includes ‘health information’, as defined in section 6 of the Health Records and Information Privacy Act 2002 (HRIP Act). This means that for the purposes of the MNDB Scheme, ‘personal information’ includes information about an individual’s physical or mental health, disability, and personal information connected to the provision of a health service.

When is personal information “Held” by an agency?

Under section 59C of the PPIP Act, personal information is ‘held’ by a public sector agency if:

- The agency is in possession or control of the information, or

- The information is contained in a state record for which the agency is responsible under the State Records Act 1998.

The Guide to managing data breaches in accordance with the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 (NSW) (Guide to managing data breaches) provides advice on the management of data breaches involving information that is ‘held’ by one or more agency.

The MNDB Scheme does not generally apply to private sector service providers providing services on behalf of government. This is because information held by a private sector service provider is usually ‘held’ by the service provider and not by a public sector agency. However, in some circumstances, information in the hands of a private sector service provider may still be ‘held’ by an agency if the agency retains a legal or practical power to deal with the personal information – whether or not the agency physically possesses or owns the medium on which the personal information is stored. This will most commonly arise in the case of software-as-a-service contracts or cloud service provision where the agency has control over the use and access to the information. See the Guide to managing data breaches for further advice on this issue.

2.4 Unauthorised access

The unauthorised access to personal information occurs when personal information held by an agency is accessed by someone who is not permitted to do so.

Unauthorised access can occur:

- Internally within an agency – for example, an employee browses agency records relating to a family member or a celebrity without a legitimate purpose.

- Between agencies – for example, a team at one agency may be provided with access to systems and data at a second agency as part of a joint project. Unauthorised access may occur if a member of the team were to use that access beyond what is required for their role as part of that project.

- Externally outside an agency – for example, personal information is compromised during a cyberattack and accessed by a person external to the agency.

2.5 Unauthorised disclosure

Unauthorised disclosure occurs when an agency (intentionally or accidentally) discloses personal information in a way that is not permitted by the PPIP Act or HRIP Act.

For example, an unauthorised disclosure may occur where:

- A system update results in the unintended publication of customer records containing personal information on an agency’s website.

- An agency intends to provide de-identified information to a researcher but accidently sends the data with personal identifiers included.

- An agency provides personal information to the wrong recipient regardless of whether the information was viewed or accessed by the recipient.

- A database hosted in a cloud environment or a web facing application containing personal information does not have appropriate access controls and personal information in the data set is visible and accessed by unauthorised individuals.

Unauthorised access and disclosure are not mutually exclusive and may occur as a result of the same breach or as part of a chain of events. For example, if a malicious external actor gains unauthorised access to agency records during a cyberattack, and steals information from those records, this may amount to unauthorised access to, and unauthorised disclosure of, the personal information held within those records.

2.6 Loss

Loss refers to situations in which personal information is removed from the possession or control of the agency. Loss may occur because of a deliberate or accidental act or omission of the agency, or due to the deliberate action of a third party. For example, personal information might be lost when:

- An agency sells or disposes of a physical asset (such as a laptop or filing cabinet) that still contains personal information.

- An agency employee accidentally leaves a device containing personal information on the bus.

- A device containing personal information is stolen from agency premises or an employee’s home.

The loss of personal information will only result in an eligible data breach where such loss is likely to result in unauthorised access or disclosure of this information. If the personal information is inaccessible due to security measures or because the information is retrieved before it is accessed or disclosed, then it is unlikely that an eligible data breach has occurred.

Examples of this may include where:

- A password protected laptop containing client files is left on a bus but is handed into the depot and the agency is able to retrieve the laptop which has not been accessed.

- A USB containing personal information is lost but is both encrypted and password protected.

- A tablet device containing client records is stolen from an employee’s home, but it is only accessible via multifactor authentication.

As the loss of personal information in the above examples did not result in an unauthorised access or disclosure, no eligible data breach has occurred.

In some cases, a loss that results in serious harm to an individual may not necessarily amount to an eligible data breach. For example, where customer records are unintentionally deleted from a records management system, resulting in the denial of a particular service to those customers. Although this would not be an eligible data breach and notification is not mandatory in this scenario, it is nonetheless recommended that agencies consider voluntarily informing individuals of the loss of their information where there is a risk of serious harm.

2.7 Reasonable

The term ‘reasonable’ is not defined under the PPIP Act and will therefore bear its ordinary meaning. Whether something is considered ‘reasonable’ will depend on the facts and circumstances in each case.

Whether an employee or officer has ‘reasonable grounds to suspect’ is an objective test. The High Court has observed that whether there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to support a course of action ‘requires the existence of facts which are sufficient to [persuade] a reasonable person’, it ‘involves an evaluation of the known facts, circumstances and considerations which may bear rationally upon the issue in question’.[4] As that indicates, there may be a conflicting range of objective circumstances to be considered, and the factors supporting the presence of ‘reasonable grounds’ should outweigh those against that conclusion.

For example, an information security officer observing unusual access to agency information systems by a colleague who is known to be away on leave and unlikely to log on to work while absent may give rise to ‘reasonable grounds’ to suspect a data breach that warrants reporting to the head of the agency.

To constitute an eligible data breach under the MNDB Scheme, an employee or officer must be satisfied that ‘a reasonable person’ would conclude that the data breach would be ‘likely to result in serious harm’ to affected individuals. A ‘reasonable person’ is a hypothetical individual who is properly informed with sound judgement.

Further discussion of what may constitute ‘reasonable’ in particular circumstances can be found throughout these Guidelines.

2.8 An individual to whom the information relates and ‘affected individuals’

When an agency determines that an eligible data breach has occurred it has an obligation to notify “affected individuals”. An “affected individual” is defined under s59D as an individual:

- to whom the information subject to unauthorised access, unauthorised disclosure or loss relates, and

- who a reasonable person would conclude is likely to suffer serious harm as a result of the data breach.

The phrase “to whom the information relates’ is not defined and should be given its ordinary meaning, i.e., the person who is the subject of the information. An individual will be an affected individual, regardless of whether the information was originally collected directly from the individual or from a third party, if the information involved in the breach is about them.

Impacts on individuals, agencies or others that are indirectly connected to the breached information (but are not an ‘individual to whom the information relates’) should be excluded from the assessment for the purposes of the MNDB Scheme. In general, an individual who is only indirectly connected to the information involved in a data breach, for example through a family relationship or community group, and who may suffer detriment following a data breach as a result of that connection, would not ordinarily be an “individual to whom the information relates”.

For example, if a data breach discloses that an individual has a serious communicable disease, members of that individual’s family may suffer serious harm (for example reputational damage or discrimination) as a result of the disclosure. However, a family member in this scenario would not be a person to whom the information relates as they are not the subject of the information disclosed.

In some cases, it may be best practice to voluntarily notify other individuals or agencies who may be significantly affected by the breach but to whom the information does not directly relate. Voluntary notification must be undertaken with caution as the release of personal information through this process may constitute a further data breach or a breach of the IPPs. When voluntarily notifying, personal information about any other individuals should be removed. If an agency believes that third parties might be significantly affected by a data breach, and that notification may assist in mitigating any harm, the agency may also elect to make a public notification.[5]

3. Assessing the risk of ‘serious harm’

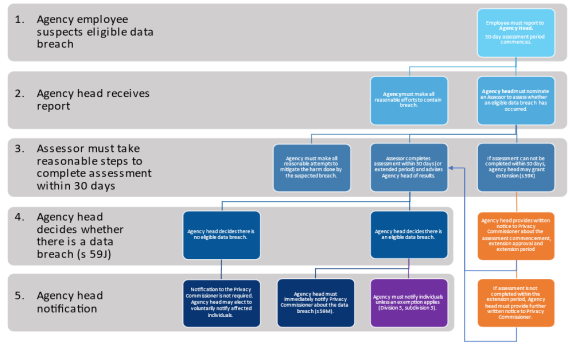

Figure 1 below provides a summary view of the assessment process, which is described in detail in this section.

3.1 Assessment process

The obligation to assess a suspected data breach is triggered ‘if an officer or employee of an agency is aware that there are reasonable grounds to suspect there may have been an eligible data breach’.[6] On becoming aware, the officer must report the data breach to the head of the agency (or to any person to whom the head of the agency has delegated functions).[7]

Following receipt of this report, the head of the agency must:

- immediately take all reasonable efforts to contain the data breach, and

- carry out an assessment to determine whether the data breach is an eligible data breach, or there are reasonable grounds to believe the data breach is an eligible data breach.

Where a breach is found to be an eligible breach, notification obligations to the Privacy Commissioner and affected individuals are triggered.

To reduce the risk of harm to affected individuals, an agency should undertake its assessment of a suspected data breach as quickly and efficiently as possible. Section 59E provides that an agency must undertake an assessment of a suspected data breach within 30 days. To meet this timeframe the person undertaking the assessment must take all reasonable steps to ensure it is completed within 30 days.[8]

The assessment timeframe commences when the officer or employee becomes aware that there are reasonable grounds to suspect an eligible data breach has occurred. The officer or employee becoming aware of a potential breach is the trigger for the time period to commence rather than when the breach is reported to, or received by, the head of the agency or their delegate.

The 30-day assessment period refers to calendar days, not business (working) days.

As there is an additional requirement for agencies to carry out the assessment in an expeditious way[9], agencies should treat the 30 days as the maximum timeframe and where possible aim to complete the assessment in a shorter timeframe.

Where the head of the agency is satisfied that an assessment cannot reasonably be carried out within 30 days, they may approve an extension of time to conduct the assessment.[10]

Where an extension is applied, the head of the agency must provide written notice to the Privacy Commissioner advising:

- when the assessment commenced, and

- that the head of the agency has approved an extension of time to carry out the assessment.

As a matter of best practice, the notice provided to the Privacy Commissioner should also include advice on the reason for the delay in undertaking the assessment.

If the assessment is not completed within the extended time period, the head of the agency must provide further written notice to the Privacy Commissioner:

- advising that the assessment is ongoing,

- that a new extension of time has been granted, and

- specifying the new extension period.

As with an initial extension notification, the notice provided to the Privacy Commissioner should also include advice on the reason for the delay in undertaking the assessment.

An extension of time may only be approved for an amount of time reasonably required for the assessment to be conducted.[11] When considering whether to grant an extension and when forming a view about the period of the extension, the head of the agency should consider whether the circumstances justify the delay.

On receiving such notification, the Privacy Commissioner may seek further information from the head of the agency regarding the progress of the assessment.

Early notification of breaches to affected individuals can be key to minimising the risks of serious harm resulting from a data breach. Agencies should avoid undue delay and should work to make affected individuals aware of the breach as soon as possible. For complex breaches or where significant numbers of individuals are affected, the agency may need to consider applying a triage system to notification. This might involve making notification in tranches based on the level of risk posed to the individual or the sensitivity of the information involved in the data breach.

3.1.4 Who should conduct an assessment?

The head of the agency may direct one or more persons to carry out the assessment (the ‘assessor’). Section 59G provides that an assessor may be:

- An officer or employee of the agency subject to the breach.

- An officer or employee of another agency acting on behalf of the agency subject to the breach. For example, this may include NSW agency employees under secondment or the Chief Information Officer of another agency assigned to assist based on their previous experience in assessing data breaches.

- An external party who has been engaged, whether through employment or contract, by the agency to conduct the assessment on the agency’s behalf, including the external party’s employees.

Note, if the head of the agency has reason to suspect an individual was involved in an act or omission that led to the data breach, that person is not permitted to take on the role of the assessor.[12]

3.1.5 How to conduct an assessment

There is no specific procedure by which an agency must conduct an assessment. In general, an assessment will involve the following:

- Information gathering: collect all relevant information regarding the suspected breach. This may involve contacting relevant stakeholders, identifying what information was or may have been compromised, and investigating logs or other evidence from compromised systems that may be relevant to the assessment of the suspected breach.

- Analysis: review the information collected during the previous phase to evaluate the scale, scope, and content of the suspected data breach, and its potential impact on affected individuals. The analysis should include a careful consideration of the type of information involved in the breach, the actual or potential harms that may arise for affected individuals, the seriousness of the harm and the likelihood of that harm occurring.

- Decision: come to a conclusion as to the eligibility of the suspected data breach based on the factors considered throughout the analysis.

3.1.6 Assessing breaches due to cyberattacks

When assessing data breaches involving cyberattacks, agencies may face challenges in establishing whether unauthorised access, unauthorised disclosure or loss has occurred. In these circumstances, the agency is often reliant on digital forensic evidence to confirm whether a breach has resulted in access to, or exfiltration of, personal information.

Agencies that do not have audit or activity logging enabled on their network or email servers/accounts, or that are unable to undertake retrospective traffic analysis of their internet gateway, will generally have difficulty determining whether a malicious actor who gained access to their network was able to access or exfiltrate personal information.

In these circumstances, it is recommended that agencies should adopt a conservative approach and conduct the assessment on the assumption that unauthorised access and/or exfiltration has occurred. The absence of digital evidence of access/loss does not in itself justify a conclusion that access/loss did not occur, particularly in circumstances where the agency has limited access auditing capabilities.

When assessing a data breach that results in personal information being posted to a website, agencies should ensure that the assessment considers the totality of personal information stored in the compromised server or network environment, and not just the personal information that has been posted on the web. Agencies should not assume that a malicious actor will publish all stolen personal information immediately or in one place. As recent data breaches in Australia and overseas have demonstrated, malicious actors will often publish part of the personal information stolen in an effort to coerce an agency to pay a ransom to prevent disclosure of the remaining information.

3.1.7 Concurrent obligations to contain and mitigate

During an assessment, the agency must make all reasonable attempts to contain the breach and mitigate any harm arising as a result of the breach.[13]

‘Containing’ a data breach means limiting its extent or duration or preventing it from intensifying. This could be done by stopping an unauthorised practice, recovering or limiting the dissemination of records disclosed without authorisation, or shutting down a compromised system. Containment actions can be distinguished from mitigation actions, which involve managing or remediating harms arising as a result of the breach.

Guidance on containment and mitigation measures is contained in the Guide to managing data breaches under the PPIP Act.

When the head of an agency decides that an eligible data breach has occurred, the notification process under Division 3 of the MNDB Scheme is triggered.

There are four elements of the notification process, which are explained further in the MNDB Scheme Guidance:

- Notify the Privacy Commissioner: Once an agency determines an eligible data breach has occurred, the head of the agency must immediately notify the Privacy Commissioner about the breach in the approved form.[14]

- Determine whether an exemption applies: If one of the six exemptions set out in Division 4 of the MNDB Scheme applies in relation to an eligible data breach, an agency may not be required to notify affected individuals.[15] Although Part 6A does not impose a timeframe for the head of the agency to make this assessment, the IPC expects that in most instances this assessment should occur as part of or immediately following the assessment of the data breach.

- Notify individuals: Unless an exemption applies, agencies are required to notify affected individuals as soon as reasonably practicable. Notification should be made directly to the individual concerned, their parent or guardian (in the case of children) or an authorised representative. Where the agency is unable to notify directly or it is not reasonably practicable to do so, a public notification must be made.

- Provide further information to the Privacy Commissioner (as required): Agencies may be required to provide additional information to the Privacy Commissioner, if they have been unable to provide complete information in their initial notification, if they have made a public notification, or if they are relying on an exemption.

3.2 What is serious harm?

The term ‘serious harm’ is not defined in the PPIP Act. Harms that can arise as the result of a data breach are context-specific and will vary based on:

- the type of personal information accessed, disclosed or lost, and whether a combination of types of personal information might lead to increased risk,

- the level of sensitivity of the personal information accessed, disclosed or lost,

- the amount of time the information was exposed or accessible, including the amount of time information was exposed prior to the agency discovering the breach,

- the circumstances of the individuals affected and their vulnerability or susceptibility to harm (that is, if any individuals are at heightened risk of harm or have decreased capacity to protect themselves from harm),

- the circumstances in which the breach occurred, and

- actions taken by the agency to reduce the risk of harm following the breach.

Serious harm occurs where the harm arising from the eligible data breach has, or may, result in a real and substantial detrimental effect to the individual. That is, the effect on the individual must be more than mere irritation, annoyance or inconvenience.

Harm to an individual includes physical harm; economic, financial or material harm; emotional or psychological harm; reputational harm; and other forms of serious harm that a reasonable person in the agency’s position would identify as a possible outcome of the data breach.

While mere irritation or annoyance does not in itself amount to serious harm, emotional or psychological impacts of a data breach can amount to serious harm if they are severe.

See section 3.4.6 below for further discussion of the kinds of harms that may arise as a result of a data breach.

3.3 When is a breach ‘likely to result’ in serious harm?

Whether a data breach is ‘likely to result’ in serious harm is an objective test to be determined from the perspective of a reasonable person and on the facts of the specific breach in question. In this context, the phrase ‘likely to result’ means that the risk of serious harm to an individual is more probable than not, rather than merely possible.

Serious harm does not need to be likely for all individuals to whom the breached information relates. A data breach will be an eligible data breach if serious harm is more likely than not for a single individual or a subset of individuals involved in a breach.

An agency may determine that serious harm is likely to result for some individuals without being able to identify which specific individuals those are. This means that data breaches affecting very large numbers of individuals may be considered an eligible data breach even when the information exposed is not highly sensitive.

Although quantitative analysis has a role in assessment of likelihood, in most cases the exercise should be primarily a qualitative one. That is, agencies should avoid relying too heavily on mathematical calculations to determine the likelihood of serious harm. Instead, agencies should consider the factors which affect the risk and err on the side of notification when there is doubt as to whether a data breach is ‘likely to result’ in serious harm.

The following example is provided as an illustration of circumstances in which quantitative assessment may assist an agency in determining whether serious harm is likely. An agency might consider that across their customer base, on average, one in every ten thousand customers would be likely to experience serious harm if their home address were exposed in a data breach. This could be as a result of having a high-profile public position, having a sensitive job in corrections or law enforcement, being a survivor of family violence, or for some other reason. If a data breach occurred at that agency which exposed one million records including home addresses, the agency could conclude that approximately 100 people are likely to experience serious harm as a result, even if the agency did not have sufficient information to determine which 100 people those were.

3.4 Factors relevant to an assessment

The factors that may be relevant in assessing the likelihood and severity of harm are contextual to the specific type and form of the data breach. Section 59H provides a non-exhaustive list of factors an assessor may consider when determining the risk of serious harm resulting from a breach.

The Privacy Commissioner has identified the following additional factors to which agencies should also have regard when determining the risk of serious harm (as per s59H(a)(g)):

- The extent to which affected individuals may be particularly vulnerable to harm,

- The ease with which information can be accessed and individuals identified.

Each of these factors is explored further in this section.

Examples are provided in the sections below to demonstrate how these factors may operate. These examples are not exhaustive and should be considered as illustrative only. Whether there is a risk of serious harm arising from a data breach must be assessed based on the facts and context of each individual breach.

3.4.1 The type(s) of personal information involved in the data breach

Assessors should consider the type of personal information compromised through the data breach.[16]

Some types of personal information carry more inherent risk than other types. Financial information and health information are two categories that generally carry a greater risk of serious harm. For example, the disclosure of contact details (such as a phone number or email address) on their own is unlikely to result in serious harm for most people, while disclosure of financial information, such as credit card or bank account numbers, is more likely to lead to harm in the form of fraud or financial crime.

Additionally, some combinations of personal information carry more risk than others. For example, disclosure of contact details for individuals combined with information that those individuals have recently sought support for problem gambling may expose those individuals to a greater risk of embarrassment or of being targeted by a scam.

Combinations of multiple types of personal information in a record or data breach affected data set also create an additional risk of identity takeover or impersonation fraud for individuals. For example, a combination of name, address, telephone number and date of birth could be used in impersonation fraud to bypass the know-your-customer controls of a bank or government agency and gain access to the customer record for a breach-affected individual.

In considering the harms that certain types of information might pose, agencies should consider the potential for personal information to be combined with other publicly available or observable personal information.

Data breaches involving the full or partial details of government-issued identity documents or credentials, such as driver licences, Medicare cards or passports, create significant additional risks for individuals. The details of these identity documents are often collected by agencies as part of their know-your-customer controls and are verified through the Document Verification Service. Criminals who obtain the details of government-issued identity documents can easily use these details to commit fraud. This in turn can cause significant harm to the relevant individual, by impacting their credit rating or resulting in the defrauded organisation seeking recovery of costs from them.

Where a data breach involves government issued identity documents agencies should take a cautious approach and assume that there is a risk of serious harm for the individuals affected.

3.4.2 The sensitivity of the personal information involved in the data breach

Assessors should consider the sensitivity of personal information that has been compromised by the breach.[17]

Special restrictions apply to the disclosure of some types of personal information based on their sensitivity: an individual’s ethnic or racial origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership or sexual activities.[18] These types of information are considered sensitive because of the specific risks to individuals that may arise from unauthorised use or disclosure, or loss of this information by an agency. Data breaches involving these types of personal information may be more likely to result in serious harm.

As noted in the previous section, it is important to remember that there are other types of information that may not typically be categorised as ‘sensitive’ but which may pose a significant risk of harm to an individual in a given context. Identity documents or credentials that may be misused and information about vulnerabilities of an individual that could be exploited are examples of this.

Not all information within a broad class will have the same level of sensitivity. Although health and financial information may be considered inherently more sensitive, the actual risk presented by a piece of information will depend on the context and the information itself. For example, generally a patient list for an audiology clinic might be considered less sensitive than a patient list for a drug treatment centre due to the reputational impact that may result for affected individuals. However, for an individual employed in a field that requires full hearing ability, disclosure of this information may have a more significant impact.

A combination of personal information is also typically more sensitive than a single piece of personal information. Data breaches involving health information, identity documents, or financial information can all cause harm on their own, but if combined, will likely present greater risks to the affected individuals.

3.4.3 Whether the personal information is or was protected by security measures

Assessors should consider the extent to which information subject to unauthorised access or disclosure is protected by security measures.[19]

Strong encryption may significantly reduce the likelihood that personal information will be misused even if it is lost or accessed or disclosed without authorisation. Other security measures, such as access controls (using strong passwords, multi-factor authentication (MFA) or biometrics) and remote wiping capabilities can also be effective when combined with strong encryption. The level of protection offered by a particular technological solution may change over time and agencies should monitor the use of technology to ensure its continued effectiveness.

Assessors should consider (and if required, obtain technical advice on) the likely effectiveness of the specific security measures that were in place, taking into account the anticipated capabilities of the attacker. For example, if data stolen by a sophisticated hacker is protected by a relatively weak encryption protocol, it may not be reasonable to expect that encryption to be effective in reducing or preventing harm. Whereas if a laptop is stolen opportunistically from an employee’s car, but all data on the laptop is protected in line with an industry-recognised secure encryption standard and a strong password, MFA or biometric access control, it may be reasonable to conclude that the likelihood of a thief being able to gain access to the stored information is low and so the risk of serious harm is low.

In cases where disclosure was inadvertent or accidental, an agency should have regard to whether the unauthorised recipients of the personal information would have the motive and/or capability to circumvent any security safeguards applied to the information. For example, if a threat actor holds both encrypted data and the encryption key needed to decrypt that data, the agency should not assume the data is secure.

3.4.4 The persons who have, or may have, had access to the information

Information about the identity or motives of the person/s who have or may have had access to the personal information can enable an agency to better assess the likelihood and severity of harm to affected individuals.[20]

Personal information obtained through a targeted cyber-attack by a known cybercrime group may be very likely to be published or misused in a way that causes harm. Cyber-attacks involving ransom demands are usually accompanied by threats of the harms that will result from publication on the dark web. Agencies should consult with cyber security experts in assessing the seriousness of these threats and consequential harms. Agencies should also report ransom demands to Cyber Security NSW, other cyber authorities (where relevant) and police.

By comparison the same information accidentally sent to a lawyer at a law firm providing services to an agency may be much less likely to be misused. In this case it might be sufficient to request and seek written confirmation (by way of a statutory declaration or undertaking) that the information has been deleted from all sources (including deleted folders) to be satisfied that serious harm is unlikely.

If personal information is made public, it is much more likely that someone, somewhere will have the skills and motive to misuse it.

Any relationship between the recipient of compromised information and the individual to whom the information relates can have a bearing on the likelihood of harm eventuating from the breach. Certain types of information (for example, information about sexual preferences or practices) may be highly distressing or embarrassing if disclosed to a colleague or family member but may be much less impactful if disclosed to an unknown third party. Similarly, an individual’s postal address may be of little consequence in the hands of an unrelated third party but may present a very high risk in the hands of a former partner where there has been a history of family violence. However, it cannot be automatically assumed that a disclosure to an unknown third party will not result in some level of harm.

3.4.5 Likelihood the person/s had malicious intent or capacity to circumvent security measures

Whether the compromised personal information is in the hands of people whose intentions are unknown, or possibly malicious, can have a bearing on the level of potential risk.[21]

As discussed in the previous sections, the risk of harm arising from a data breach will be higher when the recipient of the information is a sophisticated actor and has demonstrated malicious intent. For example, where a breach has occurred as the result of a deliberate and targeted cyberattack, it will usually be the case that the risk of harm is higher than where the cause was accidental or inadvertent (for example, the accidental disclosure of information to an unintended recipient). The more sophisticated the threat actor, the more likely they will be able to circumvent security measures and sell or exploit lost or stolen data effectively.

3.4.6 The nature of the harm that has occurred or may occur to the affected individuals

The exposure of personal information during a data breach can result in a range of harms to the affected individuals.[22] Harm can be physical, financial, emotional, or reputational. The particular characteristics and circumstances of the individuals affected may also impact the risk of harm. A person may be impacted by just one type of harm or by a combination of harms as a result of a data breach event and this may be a relevant factor for consideration as part of the risk assessment. The risk of harm may also be increased where the affected individual has been impacted by a previous data breach.

Examples of harm that may arise from a data breach include:

- Identity theft or fraud: Identity theft occurs when someone uses another person's personally identifying information such as their name, date of birth, identifying numbers (for example, Medicare, passport or driver licence number), or credit card number, without their permission, to commit fraud or other crimes. Identify fraud can encompass a range of activities, including the unauthorised use by one party of another party’s personal information to:

- create fake identity documents in the individual’s name,

- apply for grants, loans and benefits,

- port a telephone number to a new device,

- create a social media profile,

- apply for real identity documents in the person’s name, but with another person's photograph,

- open a bank account,

- obtain a credit card,

- apply for a passport, or

- conduct illegal activity.

- Financial loss: Financial loss involves monetary loss or a loss in the value of something. Financial loss may be a result of scams or identity theft, or may be incurred by an affected individual in remediating or responding to the impacts of a data breach, for example:

- Direct loss of money or assets, for example where compromised information is used to help target and lend authenticity to a scam, or to enable fraudulent transfer of funds or assets, or application for loans.

- Other costs incurred in responding to a breach, for example, cost to reissue identity documents, costs of counselling, fees from legal or other professional advisors retained to assist in managing impacts, cost of increased security measures or relocation expenses.

- Loss of a financial benefit, for example damage to a person’s credit worthiness through identity fraud.

- Disruption of access to government services: Data breaches may result in the loss or denial of access to vital government services, including access to utilities or health services, for example where compromised credentials have been used for identity fraud and an individual loses access to their own accounts.

- Emotional distress, embarrassment or humiliation: The loss or theft of personal information might cause significant emotional distress that has a detrimental impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the affected individual. Exposure to an increased risk of scams and identity theft (which can be long lasting and difficult to resolve) can lead to anxiety and hypervigilance. Similarly, loss of control over information boundaries within a person’s life — between work, social and home lives, or around private facts such as health, for example — can be distressing and humiliating. For at-risk or vulnerable individuals, the real or perceived risks of harm arising from the breach of their personal information can cause very significant emotional impacts.

- Reputational damage and loss of employment or business opportunities: A breach of personal information can result in embarrassment or damage to the personal or professional reputation of the affected individual. In turn, this may have negative impacts on an individual’s employment or business prospects.

- Physical harm, stalking, harassment or intimidation: Data breaches can result in increased risks of physical harms, stalking, harassment or intimidation. Some individuals may be more susceptible to these types of harms based on their personal circumstances or profession, such as celebrities, corrections and police officers, judicial officers, and individuals impacted by family or domestic violence.

- Family or domestic violence: Data breaches can result in an increased risk of family or domestic violence, for example when information about an at-risk person’s current address, activities or access to services is shared with a perpetrator of family or domestic violence.

The particular characteristics and circumstances of the individuals affected may impact the type, likelihood and severity of harms that may arise. Agencies should consider whether affected individuals may be particularly vulnerable or susceptible to harm. Vulnerability can be temporary or permanent and can arise as a result of either a heightened exposure to harm, or a decreased ability to protect oneself from harms.

Vulnerability may be due to a particular attribute or condition of an individual, such as their age, mental or physical health status, disability status, literacy. Some kinds of vulnerability may arise as a result of a person’s choices or circumstances such as their profession, employment/unemployment, past experiences, financial stress, homelessness or caring obligations.

Not all types of vulnerabilities will lead to greater susceptibility to harm from a data breach.

Where a data breach affects a large number of individuals, it may be impracticable to assess vulnerability on an individualised basis. However, agencies should consider the range and frequency of vulnerabilities that are present within the population as a whole (or if the breach only affects a particular sub-group, the range and frequency of vulnerabilities that are present within that sub-group).

3.4.8 Ease of identification of individuals

An important factor to consider is how easy it will be for a person who has access to compromised personal information to identify specific individuals or match the data with other information to identify individuals.

Depending on the circumstances, identification could be possible directly from the personal information breached with no special research needed to discover the individual’s identity, or it may be extremely difficult to match personal data to a particular individual, but it could still be possible under certain conditions.

Identification may be directly or indirectly possible from the breached information, but it may also depend on the specific context of the breach, and public availability of related personal details. Agencies should consider that most individuals will have some form of publicly available presence or profile that may facilitate identification of an individual from information disclosed via a data breach. This could include:

- social media accounts,

- personal websites and blogs,

- digitised newspapers and magazines, or

- genealogy databases.

Agencies should take a cautious approach and generally assume that most individuals will be identifiable from a small amount, or even a single item, of personal information.

[1] PPIP Act s59I.

[2] PPIP Act s 59D.

[3] While it is possible that an agency may experience a data breach as a result of non-compliance with the IPPs or HPPs, a breach of the IPPs or HPPs will not automatically constitute an eligible data breach. For example, a breach of the security IPP in and of itself would not necessarily amount to an eligible data breach, but it may do so if a reasonable person could conclude that an affected individual was likely to experience serious harm as a result of the breach.

[4] George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 at 112 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron & McHugh JJ); McKinnon v Secretary, Department of Treasury (2006) 228 CLR 423 at 430 (Gleeson CJ & Kirby J).

[5] Agencies may elect to make a public notification under section 59P of the PPIP Act.

[6] PPIP Act s 59E(1).

[7] PPIP Act s 59ZJ.

[8] PPIP Act s 59G(4).

[9] PPIP Act s 59E(3).

[10] PPIP Act s 59K.

[11] PPIP Act s 59K(2).

[12] PPIP Act s 59G(3).

[13] PPIP Act s 59E(2)(a), s 59F.

[14] Note that eligible data breaches that involve tax file numbers or Commonwealth Individual Health Identifiers will also require notification to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner.

[15] See the IPC Fact Sheet Exemptions from notification to affected individuals for further information on the six exemptions.

[16] PPIP Act s 59H(a).

[17] PPIP Act s 59H(b).

[18] PPIP Act s 19(1).

[19] PPIP Act s 59H(c).

[20] PPIP Act s 59H(d).

[21] PPIP Act s 59H(e).

[22] PPIP Act s 59H(f).